Marketing on Price the American Funds Way

Part 3 in a series of three posts regarding price competition. Read Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

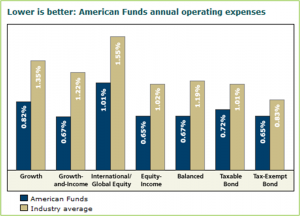

Last week I argued that there’s an ocean of opportunity for asset managers to integrate price into their marketing efforts. For a straightforward example of how this can be done effectively, look no further than American Funds, which does three things very nicely:

- Cite a commitment to low fees as one of five factors that combine to make the firm different.

- Illustrate that commitment with a simple chart of their fees vs. the competition

- Embed competitive fee information within individual product information

But we’re not American Funds. That’s the easy objection. And true. But the principles of the approach can be adopted in specific ways that suit each firm. For most every firm, one of the following is going to be true:

- Fees or other costs have been reduced, in some cases dramatically, over the past few years.

- Specific products are relatively inexpensive compared to peers.

- Specific products have significantly outperformed competitively-priced peers.

Some are always going to be more capable in keeping prices low on a broad scale. But all firms care about operating efficiently and should have evidence in hand to demonstrate that. In other words, every firm can make price a part of their value proposition. It’s up to marketers to identify the best way to do so.