“Small Data” is Becoming a Potentially Bigger Problem

“There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.” – Unknown

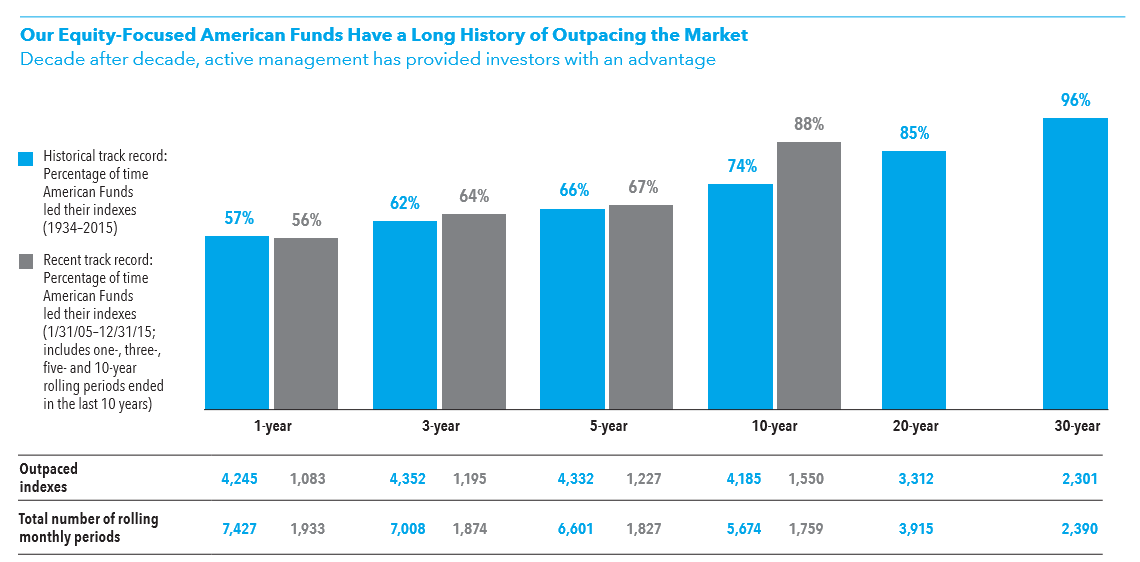

What do you see when you react to the following chart from American Funds?

At first glance the title and bar charts do their jobs. The likely reaction from most readers is probably along the lines of it looks like the majority of American Funds’ mutual funds have done a good job beating their indexes. Point made.

But, someone (like me) might linger on the chart for a few extra seconds, leading some questions to come to mind:

- What are “equity-focused” funds? Is the data set not just pure equity funds?

- Is the data gross or net of fees? If gross, how does that impact the results?

- Why is the “recent” track record defined as 10 years?

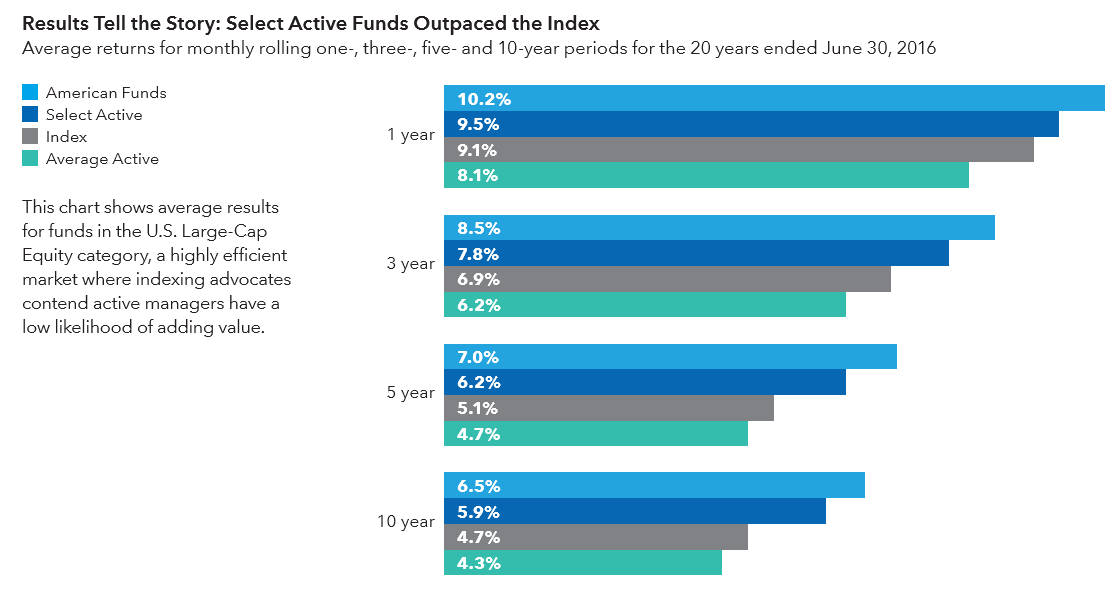

Here’s one more example that leads off a different American Funds piece supporting active management:

Again, a cursory look gives a clear initial takeaway. A bit more consideration, however, can trigger a few more questions:

- How were the specific thresholds for defining “Select Active” funds determined?

- Is the data gross or net of fees? (Yes, this question is essentially ubiquitous.)

- Why is only US Large Cap Equity included? How does the data vary for other categories?

These questions are the result of what I’ll call the industry’s “small data” issue. Small data is the information that asset managers use to support their ideas and research. It is the ever-present backbone of the countless arguments making the cases for asset classes, factors, specific mutual funds, and more.

The problem with small data is two-fold:

- The parameters and decision-making processes surrounding it are often unclear, even if someone willingly roots around the disclosures.

- There is no uniformity in the construction and use of small data between firms or even within a single firm.

Limited consistency and transparency on the context, definition, and presentation of small data can foster questions and skepticism. I (unscientifically) wonder if firms are unintentionally making it easier for people to doubt what they see or view such data as wholly self-serving, especially given people’s general distrust of marketing messages.

Despite the burden of disclosure, the use of small data makes me think firms might benefit from a more overt approach to communicating the context around the data they present. Clear, prominent, and consistent presentation of the key parameters and rationale for a data set may both reduce potential skepticism of that data and earn firms implicit credit for being up-front with clients.